In the middle of her therapy session, Armin Schnider’s 63-year-old patient got up to leave, explaining that she had her own patients to see. She thought that she was a staff psychiatrist in the neurorehabilitation unit at the University Hospital of Geneva, not a patient with brain damage after a rupture of an aneurysm.Other times, she believed that she had to organize a large, formal reception that evening. Once, she slapped her husband when she found her refrigerator empty: where was the food she had bought for the event? But there was no event, no food—even though she believed, adamantly, that there was.

Advertisement

This patient was confabulating, which loosely defined, is when a person says something that isn’t true. Schnider is a neurologist who has been studying confabulation for more than 20 years, and his work has focused on confabulation as a result of focal brain damage, or damage to one small area of the brain. But confabulation can occur from syphilis, encephalitis, brain tumors, hypoxia, schizophrenia, dementia, and more. One of the earliest reports of confabulations was from so-called Korsakoff psychosis, which results from chronic alcoholism. It can also be found in persistent déjà vu or other neurological disorders, like anosognosia, a condition when people are not aware of their own illness. In some extreme cases, people can be unaware that they are paralyzed and confabulate to their doctors when they are asked to move their limbs.(In an interview with Errol Morris, neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran described a female patient who was completely paralyzed on her left side. When Ramachandran asked her if she could move her left arm, she insisted she could, though she clearly couldn't. When he lifted her left arm and asked her whose arm it was, she said: “That’s my mother’s arm.” Ramachandran said, “Well, if that’s your mother’s arm, where’s your mother?” The patient looked around confused, and said, “Well, she’s hiding under the table.”)“Within all these groups of people who make those confabulations, there are those that just give wrong responses and those who so much believe in it, they actually confuse reality,” Schnider says. “That's the phenomenon that I have particularly studied.“

Advertisement

These are people who don’t just give the wrong answers to questions when asked, or can’t remember specifics about their life, but who think that they are in another place or another year. They do not know where they are or what their role is. And most importantly: They actually act according to their false ideas. They leave mid-therapy session to try and find their patients. Or, like one 45-year-old tax accountant, try to leave the hospital saying there was a taxi waiting for him to take him to a business meeting. Sometimes he would instead say he was going to meet a friend to do some woodworking in the forest.It’s generally agreed that most confabulations aren’t random. Woodworking was an old hobby of the tax accountant's. The 63-year-old woman had worked as a psychiatrist and had been married to a state official and had often planned large receptions, decades earlier in her life. Some very rare patients have what are called "fantastic confabulations," which have nothing to do with reality. But, typically, confabulations are events or behaviors from the past that people bring up and apply to the present.This is why Schnider finds these patients fascinating to study. Confabulation isn’t just someone spouting nonsense, it’s a true confusion of reality, of past memories and identities. It could give clues into how our brains—in everyday life—reckon with fundamental facts: who are you, what’s your job, what year is it, where are you now? Knowing these basics seems like a given, but the research on confabulation shows it is not, and further, that our grasp on reality may be more tenuous than we’d like to believe.

Advertisement

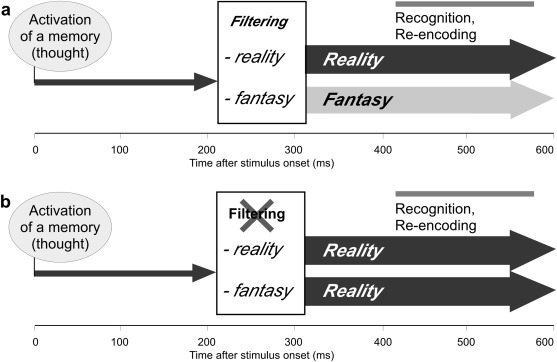

Schnider has found that confabulation is more frequent in patients with lesions in a specific section of the anterior part of the brain. In his patients that confuse reality, most have a lesion in either the orbital frontal cortex, a part of the brain just above the eyes, or in an area of the brain that has a direct connection to the orbital frontal cortex.From his decades of work, he’s come up with a theory for confabulation called orbitofrontal reality filtering. He proposes that when memories and thoughts activate in your brain, the brain must decide if those thoughts relate to the present reality or not. He thinks this is a completely pre-conscious process, and he tells me that he’s recorded it using EEG.He puts people repeatedly through a test called a continuous recognition task. You would see a long series of pictures and indicate when you've seen a picture before in that session. The first time you do it, it’s simple: you just say when a picture has been repeated and is now familiar to you. Then, when you repeat this task with all the same images, familiarity isn’t enough. You have to be able to distinguish whether you’re seeing a repeat image in this current run—the present reality—or if it was in the run before it.Healthy people can do this quite easily. What Schnider has found, he says, is that the brain activity showing someone is registering and recognizing an image can be seen at around 400 to 600 milliseconds. But once the brain additionally has to determine if an image is relevant now or from the past, he sees another, earlier signal, at 200 to 300 milliseconds. "Even before we recognize the precise content of an upcoming memory or thought, the orbitofrontal cortex has already decided whether it refers to ongoing reality or not," he says. This is the orbitofrontal reality filtering, and it's happening in the same parts of the brain that are damaged in patients who confuse reality.

Advertisement

“It's a pre-conscious process,” Schnider says. “Before we even know what we think, the brain has already decided whether the upcoming thought relates to present reality or not.”

Say a memory of being in college springs up for me. My brain will filter that as a memory, not as something important for my identity right now. In people who are confused with their realities, due to some kind of brain damage or disease, that reality filter is defective. Thoughts aren’t checked for their relation with reality, and are thought to be real and current.Schnider says that this is something we all do, and so observing it when it’s broken could be extremely useful. “The paradigms derived from the clinical studies have been useful to explore how the healthy brain adapts thought to ongoing reality,” he says.Patients with confabulations have another unique quality: they don’t realize their confabulations are untrue, even when circumstances don't play out as they say. Take one patient Schnider had, a young lawyer who had limbic encephalitis, or inflammation of the brain. She was convinced that she had to go to court. She spent her days in the hospital preparing for her court appearance, and believed that the hospital was actually her law office. She thought that in the next rooms, her colleagues were also preparing the case. She would search the hospital floor for her co-workers and her files.In a healthy person, Schnider tells me, if we believed our coworkers were in the next room, and then went next door and didn’t find them there—that would help us to realize that our idea was wrong and we wouldn’t pursue it anymore. But for people with confabulation, that doesn’t work. Even when faced with not finding her colleagues, files, or ever appearing in court, this patient continued to be convinced of her reality.

Advertisement

Another patient Schnider saw was a 58-year-old woman who stood up during her examination and said, “I’m terribly sorry, I have to feed my baby,” and left the room. Her “baby” was 35 years old at the time. When she couldn’t find her “baby” in the ward, again, that didn’t help her to understand that what she believed wasn’t true.Ivan Pavlov, a pioneering Russian physiologist (of Pavlov’s dogs), showed in the early 20th century that there is usually a learning process that takes place when an anticipated outcome doesn’t happen. This learning leads to an eventual abandonment of whatever that behavior is. Say you were hungry and pushing a lever for food. If that lever never produced food, you would eventually stop pushing the lever. This is called “extinction.” People with confabulation seem to have lost that learning process.How could they not change their mind when their belief is so clearly challenged? When the baby is not there, the law documents and colleagues are nowhere to be found? It's hard to imagine. So, Schnider asks me: “You’re in New York, is that right? Could you convince yourself that in fact you’re in Los Angeles? If somebody tells you, ‘Don’t be worried, you have brain damage. In fact it’s not 2018, but it’s 2025.’ No. Nobody could convince you of something you know to be untrue, that it’s now 2025.”He’s right—even the best debater would have an impossible task if they tried to convince me I wasn’t in New York, if I was sure that that’s where I was. And that’s how it feels to the confabulating patients. “They're convinced it's another year,” he says. “Or, they're convinced that they have to go to their office and work there. It's very stressful thing for these patients. They have no way of correcting this perception.”

Advertisement

Still, Schnider says that most of his patients with this severe form of confabulation will find their way back to reality. That’s because in many of his cases, confabulation isn’t the result of a progressive disease (though it can be a component of one) but a result of traumatic brain injury, like aneurysm rupture, or encephalitis. They may still have a memory disorder later, but their grasp on knowing who they are, when it is, what they are doing, returns.To Schnider, this (and the fact that only a minority of patients with lesions, around 5 percent, will confuse reality and confabulate) indicates that the system for reality filtering must be redundant somehow—meaning other cells must be able to take over the task of determining what’s relevant and what’s not. “That is the good message that we can give to relatives of such patients,” he says. “Be patient. This person will find back to reality some day.” It seems to be our brain’s preference to live in reality.For future work, Schnider wants to use brain imaging to try and visualize the lack of a signal of the reality filtering process in people with confabulation. He’s tried to see if he can alter the ability of reality filtering by increasing or decreasing subject’s dopamine levels, or through transcranial brain stimulation. In both cases, he was able to slightly decrease the ability people had to do the task, but could never make anyone better at it.

Advertisement

But probably the most intriguing finding Schnider has from people with healthy brains is not his ability to influence their reality filtering but the natural variation that already occurs. His task has been given to healthy controls, but sped up, so they have to do it much faster. In that experiment he saw a huge variation between subjects—a much bigger difference than anything he saw when giving people more dopamine or running electricity through their brains.“In other words, there are people who are naturally extremely fast and rapid reality-adapters and people who have much more difficulty with this function,” he says. “This [first group] might be people who would be more reality-bound, maybe less in fantasies. Those who are much worse in this function could possibly be people who are dreamers. But up to now, this is pure fantasy on my part. We have no proof of that. What we can say is that people vary very much in the capacity to do such reality filtering.”Does that mean that you can confabulate, even without damage to the brain? Oh, absolutely, says Max Coltheart, a cognitive scientist at Macquarie University.Coltheart isn't a clinician and doesn’t treat patients, but has met many people with cognitive disorders, including confabulation. His goal has been to learn more about normal cognition from such patients.He tells me that we confabulate all the time. In a classic experiment, people coming out of a supermarket were stopped and asked to choose between various packets of panty hose and explain their choice. In fact, all the packets were identical. Still, people would say they preferred one over another, and when asked to explain why people would answer with specific reasons, like “the mesh is finer in this one.”

Advertisement

Watch more from Tonic:

“That shows us that with normal people, when you ask a person the answer to a question that they don't know, they'll make up an answer,” Coltheart says. “And making up an answer is confabulation. Confabulation is normal. It's not caused by brain damage. It's exaggerated by brain damage, but the tendency to confabulate is something we've all got.”When people ask Coltheart to remember details from his own life, he says that he knows he can’t rely 100 percent on the details, because anything he might have forgotten, he’s just filling in. “When people ask me, ‘What was it like on your first day at University? Was it exciting? What did you do? I know that, any detail I recall, a lot are to be confabulations," he says.Michael Kopelman, a neuropsychiatrist from King's College London, tells me he thinks there needs to be a distinction between what he calls spontaneous confabulation, which is usually a result of damage to the brain—this is like Schnider’s patients who spontaneously offer information that’s not true—and momentary or provoked confabulation, like the panty-hose experiment. That’s more of a normal process, he says, when you are challenging your memory through a test of some kind and your brain might fill in gaps.“Momentary or provoked confabulation occurs in situations where memory is weak for whatever reason,” Kopelman says. “Whereas spontaneous confabulation is not something we all do; it's part of a disease process.”

Advertisement

This is just one of the many slight, mostly friendly, disagreements I encountered in the confabulation field. (There was a whole issue of the journal Cortex recently dedicated to competing theories on confabulation.) It’s hard to quantify confabulation, how much they’re doing it and of what kind, since there’s still disagreement about that. Kopelman thinks there are two types of confabulation, Coltheart thinks there are three, and Schnider thinks there are actually four.Because of how many disorders and symptoms confabulation can denote, Kopelman thinks we should have a narrower definition: One that is distinct from delusions or conditions like anosognosia, because he worries they might have different underlying mechanisms. Coltheart maintains that confabulation is a more universal process, a “drive for causal understanding,” and perhaps can be used to describe many things.As for Schnider’s theories on reality-filtering, Coltheart told me that most experts generally agree, but are looking forward to the details being fleshed out. Exactly how do these fragments from past memories get evoked? How do they get put together into a coherent but false memory? He’s not surprised that patients will do the actual confabulating, but wonders: How does memory work in such a way that fragments from a variety of past memories get knitted together into a single memory?Kopelman gives me a run down of some other theories: Some have thought that people who confabulate can’t tell whether a memory is something that actually happened, or is a memory of an imagined event—something called reality-monitoring (different than Schnider’s reality filtering). There are others that suggest a weakness in autobiographical memory retrieval, or a disturbed sense of chronology. There is another new intriguing theory that advocates for a motivational factor—arguing that content of the confabulation itself is driven by something.

Advertisement

I meet one of the researchers who spearheaded the motivational theory of confabulation, neuropsychologist Katerina Fotopoulou, at a café near my apartment in Brooklyn. She was in town for a conference and we decided to talk about confabulation in person.She warned me over email that she loved confabulation, and sitting across from me she confirms it again: “I really have a love affair with confabulation, I love it,” she tells me. How can a person be in love with a reality confusing brain disorder? Well, for Fotopoulou it’s because it brings something to science that usually mediums like literature have a monopoly on: the relationship between reality and fiction.“I’m interested in the relationship between reality and fiction, but in the brain,” she tells me. "Now I deal with different types of memory confabulation and also with abstract mathematical models of the brain. But what I’m suggesting through all of this is that all reality, even perception, is fiction. The brain is largely a fiction-making organ.”Fotopoulou is part of a growing group of neuroscientists who think of the brain as a predictive organ. This means that rather than actually interpreting the large amounts of sensory information it's bombarded with at all times, it forms a lot of predictions and anticipations to create the whole of our experience in reality.She gestures to my green tea on the table in front of me. “You might think you can taste this,” she says. “But you’re not actually tasting it. Your brain is predicting how this is going to feel on your tongue, how it’s going to smell, and then it’s the model that you’re actually experiencing. Only if, for some reason, it was extremely cold or warm, then you would have a large prediction error and you would wake up.”

Advertisement

To Fotopoulou, it's not as if people who confabulate live on the outskirts of reality, and we—the lucky ones—live happily within its confines. All of our realities, to some extent, are constructed or filtered. That's an interesting way to understand our own cognition, and to gain empathy for those who do confabulate.Fotopoulou first began to work on confabulation during her first case study, a man from South Africa. She went on to work with 22 patients with extreme forms of confabulation, and from them she had a realization. It’s generally agreed that confabulations don't come out of nowhere: they’re memories from the past all mixed up together. But Fotopoulou thinks that it goes beyond this. “It can be their fantasy that they're mixing up,” she says. “It can be their dreams that they're mixing up. It can be current reality that they're mixing up, and they're projecting it to another bit of current reality.”The part of the brain that Schnider's work has implicated, that bit behind the eyes, is also involved in controlling emotions, Fotopoulou says. And so she wondered: What is the relationship between these people’s need to recreate reality and their emotions? Emotion always plays a part in how we view reality. “So what happens when you constantly recreate your memory without boundaries whatsoever, right?”For her PhD she told her patients negative stories, neutral stories, and positive stores and asked them to repeat them back to her later. She found that the patients would change—and confabulate—the negative stories to make them positive. If she told them a narrative about somebody who wasn’t being nice to their friend, for example, they would later say the story had been about being a great friend.In many cases, Fotopoulou also felt that the confabulations people came up with had to do with them expressing their thoughts, distress, and confusion. “Sometimes they're trying to tell you something that really hurts them or what they want really want,” she says. “When I interact with these patients, it's like you're having two dialogues at the same time. One is what's being said and the other one is the latent content.”It’s not surprising to hear that Fotopoulou comes from a psychoanalytic background too—but she emphasizes that she still very much belongs in the neurophysiological camp: She thinks that confabulation is coming from a disorder in the brain. She just thinks that beyond simply diagnosing it as such, the content of the confabulations can be meaningful; either they’re skewed to positive over negative, or they strive to make a person’s narrative cohesive or make sense. She doesn’t deny that sometimes they may mean nothing at all.Kopelman tells me that in his experience, not everyone’s confabulations are always positive. Sometimes people get hung up on very unpleasant memories, like funerals or a frightening experience during war time. “There is often an affective bias, and it's often positive, but it can be negative,” he says. “Moreover, there were quite a lot of memories which we rated as fairly neutral, so there is a bit of a bias to remembering pleasant stuff, but it's not the only thing.”Still continuing to ask deeper questions about confabulation, probing its meanings, asking where it comes from and how it works will undeniably lead to rich insights in the functioning of our own memory, memory retrieval, reality monitoring and filtering, and more.As I continue to sip my green tea—and believe I am tasting it—I can see why Fotopoulou is so enamored with confabulation. It's a beautiful example of how fragile our hold on reality is. The field of confabulation doesn't just reveal how people with brain damage don't have a grasp on reality, it shows how we all don't. And in a world of absolutes and polarity, it suggests we should all spend a little less time being "sure."I ask Fotopoulou if her work changed the way she lives in the world if she believes that most of our experiences are a kind of fiction. She says that knowing something is an illusion doesn’t prevent you from seeing it, so in the end, there’s not much to change.“The only difference is you know it's an illusion," she says. "But you would still have the consciousness, the subjective feeling that it's like you see it. I think it's the same for me, generally, within the domains of memory or perception, or of reality as a whole. I know it's a construction, but I know the construction's good enough because that's what it is. That is as good as it gets.”Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of Tonic delivered to your inbox.