Ina Peters / Stocksy

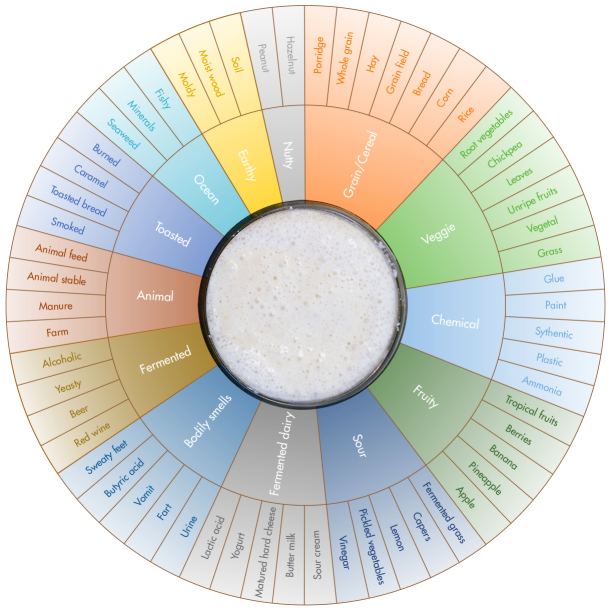

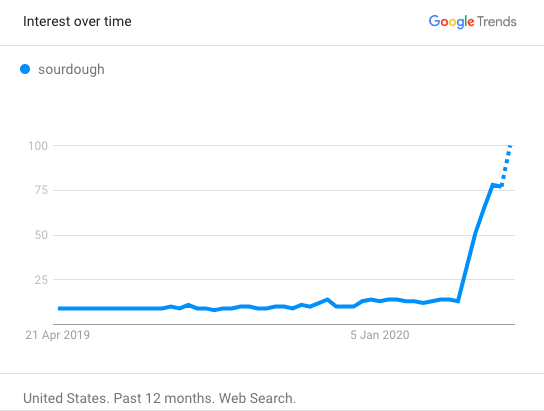

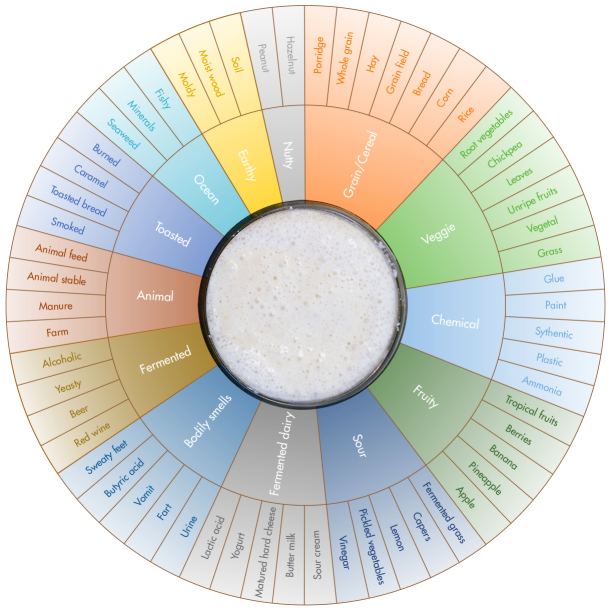

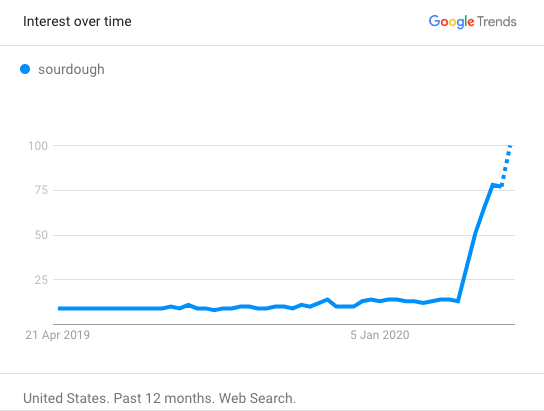

On the morning of the Turkish holiday, Hıdırellez, female bakers in the village of Ulubey wake up early to get an important ingredient for their sourdough starter, the same way their mothers and grandmothers did before them. Karl De Smedt, the world's only sourdough librarian, recorded the tale when he visited them."When the dew drops fall on the leaves before sunrise for the first time, these drops are collected in a cup like this and then it’s used to start [the bread],” one of the bakers told him. After tasting their bread, De Smedt concluded: "It's a dream."Another bakery De Smedt went to in Turkey is nestled high in the mountains. There they make sourdough bread from an ancient Turkish wheat variety and bake it in a wood-fired oven for four hours. The large loaves end up weighing between eight and 10 pounds. Though both breads are made with traditional practices from the same country, De Smedt found them to be remarkably distinct—in aroma, flavor, and texture.This is partly because the microbial life that helped create each bread was different. Sourdough is any bread that’s made from a starter populated with wild yeast and bacteria. When you mix flour and water and let the mixture sit out for several days, microbes reliably colonize the sticky substance, causing the concoction to expand and bubble. This is the starter. Once mixed into bread dough, the yeast and bacteria eat sugars and produce carbon dioxide, helping the bread to rise (this process is called leavening). Humans have known for thousands of years that a starter helps make airy, fluffy, bread.Bakers everywhere have long claimed that their starters are special, pointing to their climate, their water, or their flour as the reason. And yet it’s still a mystery what truly does make a sourdough special. Nor do we know which exact yeast and bacteria make a given starter their home, and why, said Lauren Nichols, an evolutionary ecologist at NC State University, or how that affects the end result.A new citizen science project called Wild Sourdough will be investigating this mystery. Nichols, and her NC State University colleagues Rob Dunn, Anne Madden, and Erin McKenney, will guide even novice bread makers through making a starter over 10 days, and then collect data from those starters—all for the sake of learning about the microbial life that gives each starter its unique characteristics. People will report how much and how fast their starters rise, take two photos, and describe the smell of their starters using the aroma wheel below. Wild Sourdough is part of the Global Sourdough Project, which has been ongoing for about three years, studying hundreds of sourdough starters around the world.It's perfect timing as bread baking, and sourdough in particular, has skyrocketed in popularity during the social isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic. Statistics that Reddit provided to VICE showed that the subreddit forum r/Sourdough, with 67,000 subscribers, has seen activity go up by more than 170 percent since January 1. As Eater reported, the number of people searching for “bread” hit an all time high at the end of March. Similarly, searches for sourdough have increased:

Wild Sourdough is part of the Global Sourdough Project, which has been ongoing for about three years, studying hundreds of sourdough starters around the world.It's perfect timing as bread baking, and sourdough in particular, has skyrocketed in popularity during the social isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic. Statistics that Reddit provided to VICE showed that the subreddit forum r/Sourdough, with 67,000 subscribers, has seen activity go up by more than 170 percent since January 1. As Eater reported, the number of people searching for “bread” hit an all time high at the end of March. Similarly, searches for sourdough have increased: “Sourdough is one of our most ancient technologies," Madden, a microbiologist, said. "And yet we don't even know all of the species of microorganisms that are involved that help us create the breads we love to eat."About 150 years ago, many larger baking operations switched to commercially made baker’s yeasts. That makes it easier to produce mass quantities of bread, but these yeasts lack the intrigue of wild ones.When scientists have investigated what microbes are present in wild sourdough starters, they’ve found an incredible amount of biodiversity, and often ended up discovering new lactic acid bacteria—the type of bacteria usually found in sourdough. Even sourdough samples from the same regions of the world can have very different species present.De Smedt, in his role as sourdough librarian, has seen (and tasted) this diversity first hand. He has traveled all over the world tasting and smelling breads; you can watch in his short documentary-style videos.He brings samples back to the Puratos Sourdough Library, within the Center for Bread Flavor in Saint-Vith, Belgium. It currently holds samples of sourdough cultures from 128 bakers around the world, along with thousands more in their online collection, where anyone can register their sourdough.They have isolated and found more than 800 strains of wild yeast and lactic bacteria, which are then frozen and stored. The original starters are also kept in refrigerators and fed every two months with the original flour they were made with so that sourdough diversity from all over the world can be preserved, the same way other seed banks preserve the biodiversity of plants and agriculture.Every submission to Wild Sourdough will help explore this biodiversity further. It won't tell the researchers exactly which microbes are present, because they're not doing any gene sequencing due to the pandemic, but they'll learn about the characteristics of a given starter.“Sort of the personality of the yeast and bacteria that colonize," Nichols said. "It'll give us a sense of the diversity and if there are certain kinds of starters that you find in certain places or that come about from using specific kinds of grains.”The flour used is thought to play a role in which bacteria and yeasts colonize a starter, as is the environment it’s created in. Warmer or cooler temperatures could promote the growth of different bacteria, or different ratios of bacteria in a given population. Two sourdoughs may have the same dominant bacteria, but the supporting cast could vary.The yeast in a sourdough is likely to be influenced by where you live, Madden said—a sourdough in Germany will have different yeasts than one in Australia. But intriguingly, bacteria don’t seem to follow those same rules.“While it may seem simple to fill out a few questions, we’ll actually be getting a lot of robust data,” Madden said.Learning more about the microbial world could lead to more than just delicious bread. The vast majority of microbes, not just in sourdough, have not been named. “We only even know some exist because we've sequenced their DNA," Nichols said. "We can't grow them in the lab. These microbes are surrounding us every day, whether we want them to or not, and are affecting our lives.”There’s universal recognition that our microbiomes, the microbes that live in and on us, play an incredibly important role in our health, but we still know very little about that ecosystem of bugs.“The beauty of sourdough is that it's this simple system that we actually can study and we know just enough about it that we can ask more pointed questions,” Nichols said. “By learning something about how microbes interact in starters, we can start to tease apart bigger questions about the microbes that are surrounding us and influencing us.”Starters are vulnerable to all sorts of disasters—natural, accidental and cultural, and so it's important to protect their diversity, De Smedt said. When visiting bakers, some ask him to protect their starters because they worry their successors will not continue with traditional methods of fermenting bread.In Canada, he visited Ione Christensen, a descendent of one of the first pioneers doing the Klondike gold rush back in 1896; she uses a sourdough starter she inherited from her great-grandfather. On the small jar of it in the fridge, a label reads: "100-year-old Yukon sourdough. PLEASE DO NOT THROW OUT."“On Facebook, I regularly see posts from people saying their starter was being stored in the oven and their husband switched on the oven by accident because he wanted to heat up something,” De Smedt said.During Hurricane Katrina in 2005, when bakers had to evacuate New Orleans, De Smedt said he heard of those who only took their starters with them. “They were the most precious thing that they had,” he said.

“Sourdough is one of our most ancient technologies," Madden, a microbiologist, said. "And yet we don't even know all of the species of microorganisms that are involved that help us create the breads we love to eat."About 150 years ago, many larger baking operations switched to commercially made baker’s yeasts. That makes it easier to produce mass quantities of bread, but these yeasts lack the intrigue of wild ones.When scientists have investigated what microbes are present in wild sourdough starters, they’ve found an incredible amount of biodiversity, and often ended up discovering new lactic acid bacteria—the type of bacteria usually found in sourdough. Even sourdough samples from the same regions of the world can have very different species present.De Smedt, in his role as sourdough librarian, has seen (and tasted) this diversity first hand. He has traveled all over the world tasting and smelling breads; you can watch in his short documentary-style videos.He brings samples back to the Puratos Sourdough Library, within the Center for Bread Flavor in Saint-Vith, Belgium. It currently holds samples of sourdough cultures from 128 bakers around the world, along with thousands more in their online collection, where anyone can register their sourdough.They have isolated and found more than 800 strains of wild yeast and lactic bacteria, which are then frozen and stored. The original starters are also kept in refrigerators and fed every two months with the original flour they were made with so that sourdough diversity from all over the world can be preserved, the same way other seed banks preserve the biodiversity of plants and agriculture.Every submission to Wild Sourdough will help explore this biodiversity further. It won't tell the researchers exactly which microbes are present, because they're not doing any gene sequencing due to the pandemic, but they'll learn about the characteristics of a given starter.“Sort of the personality of the yeast and bacteria that colonize," Nichols said. "It'll give us a sense of the diversity and if there are certain kinds of starters that you find in certain places or that come about from using specific kinds of grains.”The flour used is thought to play a role in which bacteria and yeasts colonize a starter, as is the environment it’s created in. Warmer or cooler temperatures could promote the growth of different bacteria, or different ratios of bacteria in a given population. Two sourdoughs may have the same dominant bacteria, but the supporting cast could vary.The yeast in a sourdough is likely to be influenced by where you live, Madden said—a sourdough in Germany will have different yeasts than one in Australia. But intriguingly, bacteria don’t seem to follow those same rules.“While it may seem simple to fill out a few questions, we’ll actually be getting a lot of robust data,” Madden said.Learning more about the microbial world could lead to more than just delicious bread. The vast majority of microbes, not just in sourdough, have not been named. “We only even know some exist because we've sequenced their DNA," Nichols said. "We can't grow them in the lab. These microbes are surrounding us every day, whether we want them to or not, and are affecting our lives.”There’s universal recognition that our microbiomes, the microbes that live in and on us, play an incredibly important role in our health, but we still know very little about that ecosystem of bugs.“The beauty of sourdough is that it's this simple system that we actually can study and we know just enough about it that we can ask more pointed questions,” Nichols said. “By learning something about how microbes interact in starters, we can start to tease apart bigger questions about the microbes that are surrounding us and influencing us.”Starters are vulnerable to all sorts of disasters—natural, accidental and cultural, and so it's important to protect their diversity, De Smedt said. When visiting bakers, some ask him to protect their starters because they worry their successors will not continue with traditional methods of fermenting bread.In Canada, he visited Ione Christensen, a descendent of one of the first pioneers doing the Klondike gold rush back in 1896; she uses a sourdough starter she inherited from her great-grandfather. On the small jar of it in the fridge, a label reads: "100-year-old Yukon sourdough. PLEASE DO NOT THROW OUT."“On Facebook, I regularly see posts from people saying their starter was being stored in the oven and their husband switched on the oven by accident because he wanted to heat up something,” De Smedt said.During Hurricane Katrina in 2005, when bakers had to evacuate New Orleans, De Smedt said he heard of those who only took their starters with them. “They were the most precious thing that they had,” he said.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

“The bacteria seem to be more influenced by how you care for your starter. Whether you leave it on the counter or in the fridge," Nichols said. "But the short answer is, we can’t explain it yet."On an interactive sourdough map from Nichols, Madden, McKenney, Dunn, and collaborators' past work, you can see how composition of sourdough starters varies across the world, and how starters that are essentially neighbors can still contain very different microbes. A person’s starter is a kind of window into the microbes that live with them in their environment.A person’s starter is a kind of window into the microbes that live in their environment.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Next week, De Smedt will go to the library to feed the sourdoughs residing there—all 128 of them. Every two months he feeds them, three times in a row with six hours between each feeding. “We start on Monday morning and we finish on Thursday evening,” he said. “It’s a long week, a lot of mixing.”He's not surprised that people are getting into sourdough during the pandemic, and hopes that the passion for sourdough continues to grow. A person gets much more than just bread out the hobby, he said.“Sourdough becomes like a pet for people,” De Smedt said. "They give it names. They talk to it. It’s something that becomes alive and you created it out of nothing by just mixing flour and water. At first, nothing happens. Then after two to three days, you see this bubbling, and it creates its own personality. You have to cherish it. If you treat it well, you get rewarded. If you do not treat it well, you will not.”Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.Follow Shayla Love on Twitter.“Sourdough becomes like a pet for people. They give it names. They talk to it."